Bronze Age Comics – an objective review of their past, present and future

I believe it was David Hartwell who said that the ‘Golden Age of Science Fiction’ was whenever the individual concerned was 12 years old. This probably applies to comics, too, which is why the so-called ‘Bronze Age’ of comics is my personal Golden Age. I was 12 years old in 1971.

But, nostalgia aside, am I right to laud the Bronze Age over other eras in the panological timescape?

The next time you buy a comic, take a look at what you’re really getting. I bet you see it as issue ‘whatever’, of ‘whatever’ comic – you’re pleased to have it: it helps fill a gap in a run, or it’s a nice example of a particular comic… you may even be looking forward to reading it, assuming it’s not imprisoned in sealed plastic... and when you do, you read the story, the letter column (maybe) and you glance at the adverts. Then you secure it away in a mylite sleeve, supported by an acid-free card, finally wrapped in a mylar outer sleeve in your humidity-controlled air-conditioned vault.

But what if you look at it through different eyes? What if you take an objective view, let the scales of nostalgia fall from your eyelids?

I felt it would be interesting to disregard completely the content of the comic strips themselves, ignoring all artistic considerations in an attempt to be as objective as possible.

That’s what this investigation is all about, and the results tell a story as fascinating as the art and stories of the comics themselves.

Note: For the purposes of comparison, I’ve stuck to one character title from one company: Batman comics published by DC, and analysed samples of this comic published from 1940 to 2006 – a span of 66 years.

*

Any comic is very much a creature of its time. So are we; so to objectively review the Bronze Age Batmans let’s first reel back the years to the summer of 1940, and take a comparative look at this title as it was at very near the beginning of its long and continuing run...

Any comic is very much a creature of its time. So are we; so to objectively review the Bronze Age Batmans let’s first reel back the years to the summer of 1940, and take a comparative look at this title as it was at very near the beginning of its long and continuing run...

The First Super-Hero Comics

example: Batman No. 2, Summer 1940: 64 interior pages for 10 cents

One of the earliest comics featuring new material with just one character, this 1940 comic makes its post 2000 descendants look like a thin pamphlets in comparison. Although it’s the same height, it boasts almost an inch extra width, and its pulp paper, with 64 interior pages, makes it about 4 times thicker than, for example, the 32 glossy pages of a 2006 Batman comic.

The interior cover ad, in black and white for ‘Johnson Smith & Co’, is a cornucopia of novelty items that have since become notorious, such as the ‘Throw Your Voice’ and the ‘Whoopee Cushion’. What caught my eye in particular was the toy ‘Diving Submarine’ – a U-Boat - , and remember that this was in 1940, before America entered World War II. Although, bizarrely, there’s an American flag at the rear. Also through this company – astoundingly – and ‘Printed Suitable for Framing’, for 10c each (3 for 25c), you can acquire a Marriage License, Doctor’s Certificate, College Diploma… and even an Air Pilot’s license! The mind boggles. All in all, 53 separate items are offered for sale on this one interior page of the comic.

After this, we turn with relief to the first story, 13 pages, then, following, a mixture of comic strips, in-house ads and a prose story. The breakdown, not in order as in the comic, is as follows:

Comic Strip Stories

1st Batman: 13 pages

2nd Batman: 13 pages

3rd Batman: 13 pages

4th Batman: 13 pages

Total Batman: 52 pages

Young Mr.Olds: 2 pages

Little Billy Pelican: 1 page

His Royal Highness: 2 pages

Other

Prose tale: 2 pages

Fantastic Facts (illustrated): 1 page

In-House DC Adverts

All Star 1, Mutt & Jeff, Superman 6: 1 page

Detective 43: 1 page

1940 New York World’s Fair Comics: 1 page

General – Action, Adventure, Detective, All-American, More Fun, Flash : 1 page

Adverts

Interior front cover – Johnson Smith & Co.

Interior back cover – Remington Typewriters

Outer back cover – Daisy Air Rifles

It adds up to 57 pages of comic strip, 3 pages of other content, 4 pages of in-house adverts and 3 pages of other adverts. In all, about 89% of the interior is comic strip story.

Comic Strip Stories

Other

In-House DC Adverts

Adverts

Comic Strip Stories 1st Batman: 15 1/2 pages

2nd Batman: 7 1/2 pages

Total Batman: 23 pages

Other Letters to the Batcave: 2 pages

So You Want To Be A Cartoonist by Joe Kubert: 1 page

In-House DC Adverts Green Lantern/Green Arrow, The Witching Hour: 1/2 page

Star Spangled War Stories The Unknown Soldier: 1/2 page

Adverts Movie Posters: inner front cover

Aurora Model Motors: 1 page

Palisades Amusement Park: 1/2 page

Be A Manager baseball game: 1/2 page

Monogram Snoopy Sopwith Camel model kit: 1 page

Moonglow Moon-Blob toy: 1 page

Raleigh Chopper Bikes: 1 page

Honor House cornocopia (the infamous x-ray specs etc): inner back cover

Hot Wheels: outer back cover

By now, a letters page has appeared. This pulls the comic readership together as a community, and adds interest to the comic for the reader. The additional feature by Joe Kubert about becoming a comic-book artist also draws the readership closer to the comic book creators and perhaps indicates that DC wishes to present a less corporate image. This could be, by then, due to the increased competition by rival Marvel Comics with its ‘Stan’s Soapbox’ and other features that gave Marvel a greater sense of closeness to its readers than DC.

The Batman strips are now 72% of the interior. A drop of 34% in 22 years, from 35 pages in 1948 to 23 pages in 1970.

example: Batman No.234 August 1971: 48 interior pages for 25 cents

All characters, logos, and images are owned and © 2011 by DC Comics They are used here for educational purposes within the "fair use" provision of US Code: Title 17, Sec. 107.

One of the earliest comics featuring new material with just one character, this 1940 comic makes its post 2000 descendants look like a thin pamphlets in comparison. Although it’s the same height, it boasts almost an inch extra width, and its pulp paper, with 64 interior pages, makes it about 4 times thicker than, for example, the 32 glossy pages of a 2006 Batman comic.

The interior cover ad, in black and white for ‘Johnson Smith & Co’, is a cornucopia of novelty items that have since become notorious, such as the ‘Throw Your Voice’ and the ‘Whoopee Cushion’. What caught my eye in particular was the toy ‘Diving Submarine’ – a U-Boat - , and remember that this was in 1940, before America entered World War II. Although, bizarrely, there’s an American flag at the rear. Also through this company – astoundingly – and ‘Printed Suitable for Framing’, for 10c each (3 for 25c), you can acquire a Marriage License, Doctor’s Certificate, College Diploma… and even an Air Pilot’s license! The mind boggles. All in all, 53 separate items are offered for sale on this one interior page of the comic.

After this, we turn with relief to the first story, 13 pages, then, following, a mixture of comic strips, in-house ads and a prose story. The breakdown, not in order as in the comic, is as follows:

Comic Strip Stories

1st Batman: 13 pages

2nd Batman: 13 pages

3rd Batman: 13 pages

4th Batman: 13 pages

Total Batman: 52 pages

Young Mr.Olds: 2 pages

Little Billy Pelican: 1 page

His Royal Highness: 2 pages

Other

Prose tale: 2 pages

Fantastic Facts (illustrated): 1 page

In-House DC Adverts

All Star 1, Mutt & Jeff, Superman 6: 1 page

Detective 43: 1 page

1940 New York World’s Fair Comics: 1 page

General – Action, Adventure, Detective, All-American, More Fun, Flash : 1 page

Adverts

Interior front cover – Johnson Smith & Co.

Interior back cover – Remington Typewriters

Outer back cover – Daisy Air Rifles

It adds up to 57 pages of comic strip, 3 pages of other content, 4 pages of in-house adverts and 3 pages of other adverts. In all, about 89% of the interior is comic strip story.

Eight Years later: the Industry Matures

example: Batman No. 47, June 1948: 48 interior pages for 10 cents

By now, after World War II, the comic book industry has become big business and content is more sophisticated. The cover price is still the 10c charged in 1940, but you get less for your money. Still the height of a 2006 comic, the width has shrunk by 4/10th of an inch to just over 1/2 an inch width wider than today’s comics. It boasts ‘a 52 page magazine’ on the cover – although that includes the covers! – but the content is somewhat reduced from the early days.

The interior cover advert is for the Roadmaster Bicycle, then follows the first story: just 10 pages.

The breakdown, not in order in the comic, is as follows:

Comic Strip Stories

1st Batman: 10 pages

2nd Batman: 12 pages (split by 2 adverts)

3rd Batman: 13 pages

Total Batman: 35 pages

Little Pete: 1 page (black & white, interior back cover)

Daffy & Doodle: 3/4 pages

Other

Prose tale: 2 pages

In-House DC Adverts

None

Adverts

Keds Sports Shoes: 1 page

P-F canvas Shoes: 1 page

Winthrop shoes: 1 page

Thom McAn Shoes: 1 page

Wildroot Hair Cream: 1 page

Bazooka bubble gum: 1 page (note the Post War name! - a lot of comics had been read by G.I.s)

Ray-O-Vac Leak proofs: 1 page

Popsicle Pete ice creams: 1 page (this is a summer comic)

Kellog’s Cornflakes: 1 page

U.S. Bike Tires: 1 page

Road Master bicycle: inner front cover

Daisy Air Rifles: outer back cover

In a new development, 6 of the above adverts are cleverly disguised as comic-strips. This not only lures the readers into giving them more attention than otherwise, but also gives the impression – on a casual flick-through – that the comic book actually contains more comics strips than it actually does! A sharp move as DC has reduced the page number of the comic, whilst keeping its price the same.

Another feature, taking up 1/3 of a page, is the DC editorial Advisory Board. In those pre- Comic Code Authority days, this was meant to reassure the parents of America that what their children were reading was worthy and wholesome. They would be impressed by such luminaries as the names of 2 professors, an associate professor of psychiatry, an acting director from the Bureau of Child Guidance, and a name from the department of English literature at New York University.

In all, now, we have 36 and 3/4 pages of stories, 12 pages of adverts, and no in-house adverts. Clearly, at that time, the DC comics were selling so well that it was more lucrative for the comic pages to be taken up by outside advertizers: in all, 23% of the comic book. The comic strip stories are now down to about 77% of the interior, from 89% in issue 2.

The Bronze Age

I’ve featured three examples from the Bronze Age to take into account the 15 cent comics, the expansion to ’52 pages’ at 25 cents, then the ‘DC Implosion’ afterwards, back to slimmer comics, but priced higher at 20 cents.

example: Batman No.222 June 1970: 32 interior pages for 15 cents

The breakdown, not in order in the comic, is as follows:

Comic Strip Stories 1st Batman: 15 1/2 pages

2nd Batman: 7 1/2 pages

Total Batman: 23 pages

Other Letters to the Batcave: 2 pages

So You Want To Be A Cartoonist by Joe Kubert: 1 page

In-House DC Adverts Green Lantern/Green Arrow, The Witching Hour: 1/2 page

Star Spangled War Stories The Unknown Soldier: 1/2 page

Adverts Movie Posters: inner front cover

Aurora Model Motors: 1 page

Palisades Amusement Park: 1/2 page

Be A Manager baseball game: 1/2 page

Monogram Snoopy Sopwith Camel model kit: 1 page

Moonglow Moon-Blob toy: 1 page

Raleigh Chopper Bikes: 1 page

Honor House cornocopia (the infamous x-ray specs etc): inner back cover

Hot Wheels: outer back cover

By now, a letters page has appeared. This pulls the comic readership together as a community, and adds interest to the comic for the reader. The additional feature by Joe Kubert about becoming a comic-book artist also draws the readership closer to the comic book creators and perhaps indicates that DC wishes to present a less corporate image. This could be, by then, due to the increased competition by rival Marvel Comics with its ‘Stan’s Soapbox’ and other features that gave Marvel a greater sense of closeness to its readers than DC.

The Batman strips are now 72% of the interior. A drop of 34% in 22 years, from 35 pages in 1948 to 23 pages in 1970.

example: Batman No.234 August 1971: 48 interior pages for 25 cents

The breakdown, not in order in the comic, is as follows:

Comic Strip Stories

Batman: 15 pages

Robin (part 1 of a continued story): 7 pages

Batman reprint: 14 1/3 pages

Total ‘Batman’: 36 1/3 pages

Other

Letters to the Batman: 1 page

Criminal Identification by Plastic Casts: 1 page

Letter to Readers by Carmine Infantino explaining price rise to 25 cents: 1/3 page

In-House DC Adverts

Jimmy Olsen Giant, The House of Secrets: 1 page

Superman: 1/3 page

Adverts

Junior Sales Club of America – Greeting Cards sales kit: inner front cover

Aurora ‘Monster Scenes’ kits: 1 page

National Diamond Sales to Military: 1 page

Folk Records/How to play Folk Guitar: 1 page

Lucky Clover Club cornocopia (including ‘zomby’ (sic) eyes): 1 page

Strat-O-Matic baseball game: 1 page

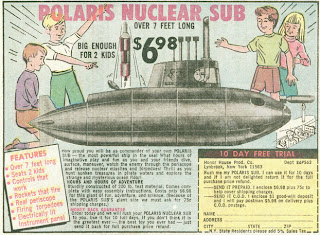

Honor House Model Polaris Nuclear Sub “big enough for 2 kids”: 1/2 page

Honor House 7 ft tall Monster Size Monsters: 1/2 page

Helen of Toy models for battle games: 1 page

Olympic Greeting Cards sales kit: 1 page

747 Jumbo Jet model: inner back cover

Mattel Hot Birds models: outer back cover

At 25 cents, a price rise of 66%, we find that the pages of new Batman (including the Robin pages) number 22, actually one page less of new story for 10 cents more! The difference is made up by a reprint Batman tale, costing DC nothing extra to the creators. In those days the writers and artists sold ‘all rights’ to their work, and were paid nothing for reprints. The extra 14 1/3 pages does bring the total up to 36 1/3 pages, an increase of 13 1/3 pages. In other words, 58% more material for a price rise of 66%. Taking into account the feature on criminal identification and the fact that, in those days, the reprinted story was usually a novelty and of interest to the reader – as it was unavailable elsewhere – I would suggest that DC more than met the value-for-money test compared to their earlier 15 cents Bronze Age comics.

However, when we compare this comic to the 1940 issue, it must be noted that, in 1940, 52 pages of original Batman story was offered (still 30% more than this 1971 comic), although I suspect 10 cents in 1940 went a lot further than 25 cents in 1971.

Comic Strip Stories

Batman: 15 pages

Robin (part 1 of a continued story): 7 pages

Batman reprint: 14 1/3 pages

Total ‘Batman’: 36 1/3 pages

Other

Letters to the Batman: 1 page

Criminal Identification by Plastic Casts: 1 page

Letter to Readers by Carmine Infantino explaining price rise to 25 cents: 1/3 page

In-House DC Adverts

Jimmy Olsen Giant, The House of Secrets: 1 page

Superman: 1/3 page

Adverts

Junior Sales Club of America – Greeting Cards sales kit: inner front cover

Aurora ‘Monster Scenes’ kits: 1 page

National Diamond Sales to Military: 1 page

Folk Records/How to play Folk Guitar: 1 page

Lucky Clover Club cornocopia (including ‘zomby’ (sic) eyes): 1 page

Strat-O-Matic baseball game: 1 page

Honor House Model Polaris Nuclear Sub “big enough for 2 kids”: 1/2 page

Honor House 7 ft tall Monster Size Monsters: 1/2 page

Helen of Toy models for battle games: 1 page

Olympic Greeting Cards sales kit: 1 page

747 Jumbo Jet model: inner back cover

Mattel Hot Birds models: outer back cover

At 25 cents, a price rise of 66%, we find that the pages of new Batman (including the Robin pages) number 22, actually one page less of new story for 10 cents more! The difference is made up by a reprint Batman tale, costing DC nothing extra to the creators. In those days the writers and artists sold ‘all rights’ to their work, and were paid nothing for reprints. The extra 14 1/3 pages does bring the total up to 36 1/3 pages, an increase of 13 1/3 pages. In other words, 58% more material for a price rise of 66%. Taking into account the feature on criminal identification and the fact that, in those days, the reprinted story was usually a novelty and of interest to the reader – as it was unavailable elsewhere – I would suggest that DC more than met the value-for-money test compared to their earlier 15 cents Bronze Age comics.

However, when we compare this comic to the 1940 issue, it must be noted that, in 1940, 52 pages of original Batman story was offered (still 30% more than this 1971 comic), although I suspect 10 cents in 1940 went a lot further than 25 cents in 1971.

example: Batman No.247 February 1973: 32 interior pages for 20 cents:

The breakdown, not in order in the comic, is as follows

Comic Strip Stories

1st Batman: 6 pages

2nd Batman: 17 1/2 pages

Total Batman: 23 1/2 pages

Other

Letters to the Batman: 1 page

In-House DC Adverts

Batman Super-Spectacular: 1/2 page

Adverts

Daisy Air Rifles: inner front cover

Easy-Bake Toy Oven: 1 page

Wayne School Home Study: 1 page

Mirobar LP stereo albums: 1 page

Corgi toys: 1 page

Honor House cornocopia inc. x-ray specs etc: 1 page

Career in Drafting kit: 1/2 page

Schwinn bikes: 1/2 page

Super-Hero Stickers: 1 page

Charles Atlas body building: inner back cover

Aurora kit cars: outer back cover

Although this is a slimmer comic, the pages of original Batman story still number 23 1/2, actually 1 1/2 more pages ( 7% more) than the 25 cents comic. But taking into account a price drop of 5 cents ( 20% ), and the loss of 14 1/3 reprint Batman pages, making the total loss in comic strip page count to just under 13 pages ( 36% less), this 20 cent comic still represents significantly less value for money than the 25 cents spent previously.

Of interest is the Toy Oven advert which is specifically targeted at girls. Did DC at this time expect a significant female readership in their Batman title? It’s more likely that the adverts ran the same across all the titles. DC had comics aimed at female readers; titles like Lois Lane, and Supergirl in Adventure Comics.

example: Batman No.652 June 2006: 32 interior pages for $ 2.50

The breakdown for this comic book is as follows:

Comic Strip Stories

1st Batman: 6 pages

2nd Batman: 17 1/2 pages

Total Batman: 23 1/2 pages

Other

Letters to the Batman: 1 page

In-House DC Adverts

Batman Super-Spectacular: 1/2 page

Adverts

Daisy Air Rifles: inner front cover

Easy-Bake Toy Oven: 1 page

Wayne School Home Study: 1 page

Mirobar LP stereo albums: 1 page

Corgi toys: 1 page

Honor House cornocopia inc. x-ray specs etc: 1 page

Career in Drafting kit: 1/2 page

Schwinn bikes: 1/2 page

Super-Hero Stickers: 1 page

Charles Atlas body building: inner back cover

Aurora kit cars: outer back cover

Although this is a slimmer comic, the pages of original Batman story still number 23 1/2, actually 1 1/2 more pages ( 7% more) than the 25 cents comic. But taking into account a price drop of 5 cents ( 20% ), and the loss of 14 1/3 reprint Batman pages, making the total loss in comic strip page count to just under 13 pages ( 36% less), this 20 cent comic still represents significantly less value for money than the 25 cents spent previously.

Of interest is the Toy Oven advert which is specifically targeted at girls. Did DC at this time expect a significant female readership in their Batman title? It’s more likely that the adverts ran the same across all the titles. DC had comics aimed at female readers; titles like Lois Lane, and Supergirl in Adventure Comics.

Sixty Six Years on: Generations Later

example: Batman No.652 June 2006: 32 interior pages for $ 2.50

The breakdown for this comic book is as follows:

Comic Strip Stories

Batman (part 4 of a series): 22 pages

In-House DC Adverts

52 (a weekly): 1 page

DC Nation (Editorial), Detective,Action,Batman,Ion: 1 page

Adverts

Planet of the Apes DVD Collection: interior front cover

Milk: 1 page

Final Fantasy VII DVD: 1 page

Artemis Fowl book: 1 page

The Sea of Monsters book: 1 page

Dungeons and Dragons Game: 1 page

Nike: 1 page

Heroclix Game models: 1 page

Anti-Drug campaign: 1 page

Pontiac car (starting at $20,490)!: interior back cover

Tomb Raider Legend: back cover

These adverts are an excellent sampling of the other contemporary interests of the time, with the interesting dichotomy of the urge to get the youth of America to drink more milk, alongside the warning of the dangers of drug abuse.

The evolution of the interior back cover advert in the comics is fascinating: in 1940 it was for a typewriter, in 1948 it was for a bicycle. In 2006 it’s for a Pontiac car. Not a model - the real thing. Is this a reflection of the vastly increased wealth of the children of America? I doubt it. More like a reflection of the perceived readership profile of Batman comics in 2006. Clearly, though, the drivers – and owners – of $ 21,000 Pontiacs are not the same as the comic book audience of 66 years ago.

At 9 interior pages, the adverts in this 2006 Batman represent a hefty 28% of the interior, whereas the sole (part) story is about 69%.

Given the vast social and technological changes over the last 66 years, what strikes me the most about these comic books is not how different they’ve become, but how similar they still are. When I hold Batman No.2 in one hand, and look across to Batman No.652 in the other, they are clearly still the same product.

And how does the value-for-money factor compare between 1940 and 2006? What would 10c (that buys a 64 page comic book) in 1940 be worth today? 10c in 1940 has the same purchase power as $ 1.39 in 2006.

Given that the 2006 comic book has half this number of pages, it should be priced at half this amount: 70c. Instead, it costs $ 2.50.

So the 2006 reader is paying comparatively x 3.5 more than the 1940 reader, for 69% story, compared to 89% story.

And, of course, the 1940 reader got 4 complete Batman stories instead of less of one part of 1 story.

It’s clear that the Bronze Age was a time of experimentation and transition, with comics going through rapid changes of format, pages and pricing in a relatively short time.

Also, and of more lasting significance, the Bronze Age comics heralded a greater awareness of comic book fandom in the publishers, as opposed to the casual readership. The offering of reprinted comic strips from decades before would be expected to have more of an appeal to comic fans than a contemporary readership. This weighting of the fans’ influence against the general reader would eventually lead to changes in comics distribution with the advent of direct sales to comic shops – a change that would in turn alter the comic books themselves (in a way that’s beyond the scope of this study).

And what about today’s successors to those Bronze Age comics?

We’re now entering another period of transition with the era of the portable digital device like the Kindle, promising a revolution in the way that the readership accesses comics. Already, the latest issues of DC and Marvel Comics are available in downloaded form for a price, either to be read full-page or panel by panel.

The comparative value of these ‘comics’, existing as electrons on a hardware device, and presumably not having any potential resale or investment value, poses interesting questions.

But whatever form comics may take in the future, the Bronze Age will remain, in objective terms, a pivotal panological era – despite all our different personal ‘Golden Age’s.

copyright. Nigel Brown

Batman (part 4 of a series): 22 pages

In-House DC Adverts

52 (a weekly): 1 page

DC Nation (Editorial), Detective,Action,Batman,Ion: 1 page

Adverts

Planet of the Apes DVD Collection: interior front cover

Milk: 1 page

Final Fantasy VII DVD: 1 page

Artemis Fowl book: 1 page

The Sea of Monsters book: 1 page

Dungeons and Dragons Game: 1 page

Nike: 1 page

Heroclix Game models: 1 page

Anti-Drug campaign: 1 page

Pontiac car (starting at $20,490)!: interior back cover

Tomb Raider Legend: back cover

These adverts are an excellent sampling of the other contemporary interests of the time, with the interesting dichotomy of the urge to get the youth of America to drink more milk, alongside the warning of the dangers of drug abuse.

The evolution of the interior back cover advert in the comics is fascinating: in 1940 it was for a typewriter, in 1948 it was for a bicycle. In 2006 it’s for a Pontiac car. Not a model - the real thing. Is this a reflection of the vastly increased wealth of the children of America? I doubt it. More like a reflection of the perceived readership profile of Batman comics in 2006. Clearly, though, the drivers – and owners – of $ 21,000 Pontiacs are not the same as the comic book audience of 66 years ago.

At 9 interior pages, the adverts in this 2006 Batman represent a hefty 28% of the interior, whereas the sole (part) story is about 69%.

Given the vast social and technological changes over the last 66 years, what strikes me the most about these comic books is not how different they’ve become, but how similar they still are. When I hold Batman No.2 in one hand, and look across to Batman No.652 in the other, they are clearly still the same product.

And how does the value-for-money factor compare between 1940 and 2006? What would 10c (that buys a 64 page comic book) in 1940 be worth today? 10c in 1940 has the same purchase power as $ 1.39 in 2006.

Given that the 2006 comic book has half this number of pages, it should be priced at half this amount: 70c. Instead, it costs $ 2.50.

So the 2006 reader is paying comparatively x 3.5 more than the 1940 reader, for 69% story, compared to 89% story.

And, of course, the 1940 reader got 4 complete Batman stories instead of less of one part of 1 story.

It’s clear that the Bronze Age was a time of experimentation and transition, with comics going through rapid changes of format, pages and pricing in a relatively short time.

Also, and of more lasting significance, the Bronze Age comics heralded a greater awareness of comic book fandom in the publishers, as opposed to the casual readership. The offering of reprinted comic strips from decades before would be expected to have more of an appeal to comic fans than a contemporary readership. This weighting of the fans’ influence against the general reader would eventually lead to changes in comics distribution with the advent of direct sales to comic shops – a change that would in turn alter the comic books themselves (in a way that’s beyond the scope of this study).

And what about today’s successors to those Bronze Age comics?

We’re now entering another period of transition with the era of the portable digital device like the Kindle, promising a revolution in the way that the readership accesses comics. Already, the latest issues of DC and Marvel Comics are available in downloaded form for a price, either to be read full-page or panel by panel.

The comparative value of these ‘comics’, existing as electrons on a hardware device, and presumably not having any potential resale or investment value, poses interesting questions.

But whatever form comics may take in the future, the Bronze Age will remain, in objective terms, a pivotal panological era – despite all our different personal ‘Golden Age’s.

copyright. Nigel Brown

No comments:

Post a Comment