|

| © WB animation. With apologies to Warner Brothers. |

by Ian Baker

The spark for the first era of UK comic fandom was kindled in October 1959 and was snuffed out twenty years later in 1979.

Without American comics importer Thorpe & Porter, UK comic fandom would never had existed. Of course, comic collecting in the UK continued past 1979, but the advent of the Direct Market signaled the death knell for the new UK comic reader, the impressionable 12-year old who could go into a newsagent and pick something off the spinner rack for no more than 10p.

Some UK price variants were still available after the demise of T&P, but these were then only available in W H Smith or through the very few Direct Market comic shops - a reduction in retail availability from 88 corner newsagents to 3 WH Smiths in Portsmouth alone.

The days of mass, cheap American comic book availability had passed, and with it the chance of a casual buyer being attracted by a comic seen hanging on a peg, or stuffed into the lower rungs of a spinner rack. The spinner racks disappeared, along with the salacious men's magazines at the top and comics at the bottom.

Thorpe & Porter defined the era ; In January 1979 there were 23 titles published by DC ; most of those titles disappeared from newsstands in the UK, and with it the feeder system for new readers.

The last T&P stamped comic was the Superboy & The Legion of superheroes #240, June 1978 - a 60 cent comic priced at 25p. (As documented by “Get Marwood & I” on the excellent UK Price Variant thread on the CGC boards).

|

| © DC. The Last T&P-stamped import? Swiped from CGC thread. |

The received wisdom in the comics industry at that time was that the average new comic reader of eleven years "aged out" at eighteen, with a complete readership turnover every seven years.

At their height, T&P were importing one million comics per month, distributed to thousands of corner newsagents up and down the country. Of the 88 newsagents alone in Portsmouth in the mid 70s, if we assume that each newsagent got 60 new comics each month - that would be 60x88 = around 5,000 new comics in Portsmouth each month for a population of 200,000, of which say 2.5% were adolescent lads aged 10-14 (sorry girls). It follows that there were 5,000 lads of comic reading age in Pompey as a market for 5,000 DC comics. If you extrapolate that to the total country population in 1975 (56.2m), then we have 1.4m lads as a possible market for a million comics imported every month.

As a twelve-year-old going on thirteen in 1972, I knew nothing of comic fandom, unaware of the work of Frank Dobson on Fantasy Trader, or the infrequent early UK comic marts since the late 1960s. My pals and I were islands with no fandom other than ourselves and a very few collectors at school. How big was that local community? Not big - or if it was big - we never knew because comic fans kept their heads down, keen to avoid the jeers of their classmates and the despair of their parents.

Things changed when I ordered Fantasy Unlimited from an ad in Exchange & Mart because it had a sales list, and discovered a whole community of fans, most of whom I was only ever to know as names on a page, yet somehow we regarded as members of an extended circle of friends.

So where were these fans - who were they - and what drove the growth of fandom in that decade of the 1970s?

Fantasy Unlimited

For the purposes of the definition of being a member of UK fandom I believe that one had to contribute to a mainline fanzine at least once.

I do believe that Fantasy Unlimited (later Comics Unlimited) was the one fanzine that most accurately reflected fan participation in the comic collecting hobby in the decade of the 1970s. Not withstanding the many other zines out there in this period, I believe that FU/CU is a reasonable barometer of the growth of UK comic fandom in that decade which ended with the termination of Thorpe & Porter.

I’ve spent an inordinate amount to time reading and re-reading every issue to note down the names, locations (where known) and role of fans involved in the creation of the ‘zine’s content - whether it on production duties, article writing, letters published, requests in the “We Want Information” section, reviewers, etc. I started first with Alan Austin’s first effort “Ad Adzine” #1 (April 1970), right through the title transitions to “Aftermath” and then to Fantasy Unlimited and later Comics Unlimited up until the final issue #53 (Feb 1983).

Over that 53 issue period, there were 483 unique contributors, of whom a core of twenty-two individuals were active participants over a period of five years or more. (Many of those names will be familiar to readers of this blog as still being active in UK fandom)

For those of you with a statistical bent, the Normal Distribution bell-curve below plots the average number of months of active participation in fandom, as characterized by writing to/writing for/being reviewed in Fantasy Unlimited.

The average duration of involvement was 13 months, with 68% of participants (one Standard Deviation) being involved for up to 3 years; 95% of fans had ceased involvement after 5 years; 99% had stopped at the 6-and-a-half year point, and the remainder stayed around. This maps very closely to the comic industry's own beliefs in regular reader turnover every seven years.

Click the image to enbiggen.

|

| © Ian Baker. Analysis of duration of fan involvement in FU/CU 1970-1979 |

If we examine the inflow of new fans making their very first contribution - getting their name in lights - it becomes clear that 1975 was a banner year for participation and fandom growth. We'll examine possible reasons for this further on.

If we plot the numbers of new participants cumulatively, the flattening of the curve of new fan involvement clearly co-incides with the cease of T&P distribution.

|

| © Ian Baker for analysis. Click to enbiggen. |

What is instructive is to see the growth curve of new contributors, with 1975 being the year when interest and active participation exploded, with 135 new fandom names added within the pages, but following the end of 1979, only 11 new names appeared over the following four years. Evidence that the demise of T&P’s business stopped the flow of new fans.

In the early 1970s, Alan Austin doubted if there were more than 200-300 serious American comic-book collectors in the UK. He had been printing 30 copies of his fanzine early in 1971, which had risen to 250 copies per issue by the end of 1972. This rose to 600 per month by the end of 1975, and by 1977 he was selling two thousand copies of Comics Unlimited per month of which almost a quarter of the readership had actively contributed to the ‘zine in some form or another.

UK Comic Fandom was a community with a strong London base from the start. But by the end of the decade, there were strong communities which had developed in other major counties. A look at the chart for England below highlights where those clusters of fan were based. Interestingly, there were some counties which never attracted a fan contribution in any form.

By the end of 1979, London & Middlesex was represented by 71 fans (plus a further 40 whose addresses were not published, but were most likely London-based), with a further 42 in the Home Counties. A further 30 were based in Yorkshire across the Ridings, with a further 22 in Lancashire, 10 in Cheshire and 10 in Nottinghamshire. The remainder were spread across the remaining counties.

My own county, Hampshire, fielded 10 active contributors, lead by the irrepressible Allan J Palmer in Basingstoke with thirty contributions over a seven-year period , and with a creditable 10 entries from SuperStuff's own Nigel Brown. (Modesty prevents me from listing my own contributions).

I’m inclined to believe that the fanbase was in direct proportion to the number of newsagents and a reflection of Thorpe & Porter’s distribution reach.

Here's the chart showing the active fanbase in England as recorded in Fantasy Unlimited as of 1979.

|

| Map © Microsoft. Analysis of data by Ian Baker |

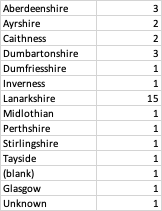

The picture for Scotland is better represented in a table (see below), where there developed a steady core of fans in Lanarkshire, mostly centered around Glasgow.

In Wales, 12 fans made a contribution over the years, of which 9 were in Glamorgan.

In Northern Ireland, 11 fans made their presence known, fairly well distributed, with the largest group of 4 based in Co Antrim.

I have no knowledge if these clusters of fans in certain counties made contact with each other.

I am interested in what drove the explosive growth of UK comic fandom in 1975. Is it just an outlier, or were there other factors at play? Or perhaps more interestingly, what caused the decline from 1976 onwards? The UK inflation rate in 1975 peaked at 24.24%, and declined only to 16.54% the following year. Comic prices had gone from 5p to 10p over this period, and the availability of colour Marvel comics had declined to avoid competition with the UK Marvel weeklies. Perhaps it was just a case that pocket money could not buy nearly so many comics, and supply issues were preventing new readers coming on board.

There’s a lot more analysis yet to be done on the data - for example, the types of questions raised in Alan Austin’s “We Want Information” column . What is clear is that in the early days questions focused on the Golden Age - that mythical time before 1959. As the years rolled by, questions were much more related to concerns of T&P distribution breaks and Non-Distributed issues of Marvel Comics. Fans were becoming educated consumers.

I don’t claim this to be an exhaustive analysis ; certainly a good read of other fanzines of the time will yield more names, but I do think the pages of FU/CU reflects the growth of UK comic fandom in its second decade.

Reading through the roll-call of names mentioned in the pages of FU/CU the names of various individuals who made the transition to the professional comics world jump out - John Bolton, Kev O'Neill, Grant Morrison, Dez Skinn, etc - along with others less well known. Other people found careers as musicians, lawyers, writers, designers, with quite a few names still to be found at London Marts today, both as dealers and punters.

If Mr J.C. Hill of Watford, Hertfordshire should be reading this, did you ever write your envisioned History of UK Comics Fandom?

UK Comic Fandom today

So how big is UK comic fandom today - if we accept that it was perhaps a couple of thousand with a core of almost 500 active participants back in the late 70s?

Is UK comics fandom just a bunch of men in their sixties and seventies trying to rekindle those days of the 1970s when anything seemed possible? Does comics fandom for the latest comics even exist? Where does an intelligent discussion of new comics today take place? Certainly not on the Social Networks I frequent.

As of a few months ago, these Facebook groups targeted at a UK audience recorded the following membership:

- 936 members of London Loves Comics

- 288 in Fanscene

- 4,200 in Marvel UK comics

- The Comic Book Group UK. 1,600

- Comics Buy and Sell UK. 4,000

- Comic Books for Sale UK. 19,000 members

Perhaps there is a substantial following today, but once you weed out the Silver Age and Bronze Age fans, and the professional sellers, the Cosplay fans, the MCU an DCEU movie fanbase, does that core set of fans of the printed page exist?

Comments welcome.

© Ian Baker, 2023