It was 50 Years Ago today....musings on comic collecting and Super Stuff in Portsmouth & Southsea in the fun 1970s. Brought to you by the SuperStuff team!

Wednesday, January 26, 2022

Belfast, Thor and growing up in the Sixties

Saturday, January 15, 2022

Where were you in ’72? Remembering when comics were “relevant”

Do you remember when comics were “relevant”?

Any discussion of social relevance in comics always lights upon the topics of skin color and social deprivation highlighted in Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76, or mentions Speedy’s drug addiction as shown in Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85 and #86. While it is true that those stories can be regarded as the high water mark for DC comic books connecting with real-world issues, they also marked the start of a decline to a blander and less challenging approach to packaging superhero material that continues to this day.

|

| Green Lantern #76. © DC Comics 1970 |

When New York mayor John Lindsey praised the “no-holds barred” approach to highlighting drug abuse depicted in Green Lantern/Green Arrow in 1972, DC had been quietly bringing “relevance” into DC comics for the past 4 years since 1968, reflecting a growing desire by a small cadre of young writers at DC to tackle the most pressing social injustices in a way accessible to a college youth disaffected and worried about going to Viet-Nam.

Over a period of five years, thirty-eight DC comics tacked the problems of the day head-on, and a further forty-plus comic stories, while less confrontational, quietly reflected the current mores within the United States ; the changing attitudes to Women’s roles in the pages of Wonder Woman and Lois Lane ; Bat Lash humourously bringing the modern hippie counter-culture to the Old West, and Tomahawk highlighting contemporary Native American concerns through the lens of Hawk, Son of Tomahawk. In addition, Mike Friedrich’s authorship of the Robin back-up stories first in Detective Comics and then subsequently in Batman brought a modern perspective to college life.

Looking back from a vantage of fifty years, I think that DC did a great job of educating me on social issues as a 12-year old. I was not an avid reader of UK-produced comics and I doubt that if I’d been a collector of solely UK comics that I would have been exposed (either consciously or sub-consciously) to the evils of political corruption or environmental concerns at such a tender age.

From 1968 to 1973, stories of relevance snaked their way through many popular DC titles, although I think it is fair to say that if you were not a fan of Justice League of America or Green Lantern/Green Arrow, the themes may have passed you by.

1968 - DC dips its toe in the water of social relevance

|

| The start of "relevance" at DC. Wonder Woman #178. © DC Comics |

It can be argued that the ascendance of “relevance” marked the start of the comics Bronze Age. Certainly, the first flag planted in the ground for “relevance” in comics was the September 1968 issue of Wonder Woman #178 “Wonder Woman’s Rival” , under the shepherding of twenty-nine year-old Denny O’Neil. Denny wrote a story in which Wonder Woman re-assesses her life and motivations, in the process relinquishing her costume in the quest to become a liberated woman. These early "New" Wonder Woman stories did not overtly push the Women’s Lib agenda. In fact, many of the stories still revolved around Diana Prince trying to hold on to Steve Trevor as a romantic beau, but the fact that DC’s most famous female superhero was embracing the new social sensibilities sent a major message to the audience. Young Denny O’Neil was quietly crafting some major changes, first under the editorship of old DC hand Jack Miller, and then subsequently under artist-turned-editor Mike Sekowsky.

Reader reaction on the letters page of Wonder Woman #181 was overwhelmingly positive, and included praise from a certain Mark Evanier. Relevance was off to the races!

Denny O’Neil was already a known advocate for the peace movement and women’s rights when he joined DC. In a later interview with Gary Groth of The Comics Journal he said “It was part of my agreement with DC that I will not be asked to write a story glorifying war because I don’t believe that war is ever a good thing and I would not feel comfortable with a military hero. I also don’t like to write romance stories. I did Millie way back when. That’s a skeleton in my closet, though. I think the way those stories are handled demeans what happens between a man and a woman.”

The following month in October 1968, Bat Lash #1 hit the stands (again written by Denny O’Neil, this time abetted on plot by Sergio Aragones, drawn by the incomparable Nick Cardy) which introduced a counter-culture Western hero – an amoral, hippie-inspired lead character – in a quietly subversive and highly enjoyable comic romp.

|

| © DC Comics . Bat Lash #1 |

1969 - Personal Responsibility and Political Corruption take center stage

And so for a period of six months over the end of 1968, these comics were quietly reshaping the landscape, until April 1969 saw the first in-your-face “relevant” DC comic in the guise of Brave & Bold #83 “Punish Not My Evil Son”, to be followed two issues later by Brave & Bold #85 “The Senator’s Been Shot!” , both from the pen of Bob Haney and the pencil and brush of Neal Adams.

|

| B&B 83 - Punish Not My Evil Son: greed is the face of evil. © DC Comics |

“Punish Not My Evil Son” involved Batman and the Teen Titans battling corruption in the oil industry, whereas “The Senator’s Been Shot!” highlighted political corruption, and marked a major turning point in establishing Green Arrow as a tough advocate for social justice. Interestingly, Brave & Bold #85 ends with Bruce Wayne, as a US Senator, arriving at the last minute to move the anti-crime bill forward, in a clear support for democracy and belief in Government. Richard Nixon is featured, two years before the Watergate allegations cast him in a very different light.

|

| © DC Comics. B&B 85. The dangers of big business corrupting Government |

|

| ©DC Still believing in Democracy before Nixon's downfall |

Writer Bob Haney was an interesting individual. Having first entered the comics business in 1948, he was very much autonomous in his writing approach under the flexible editorship of Murray Boltinoff. A brief bio of Bob published in that same Brave & Bold issue underlined that “Bob feels that the whole world of comics and animation has yet to reach maturity and proper exploitation”. I suspect that Bob Haney had much in common with the much younger Denny O’Neil, and was open to co-ordinating themes across comic lines. I think it is fair to say that DC avoided bringing contentious issues into the pages of their big mainstream money-makers (Batman, Superman, Detective, Action), but had fewer concerns about using the pages of a lesser-known Batman title like Brave & Bold as a vehicle for more ground-breaking storytelling.

The year of 1969 was rounded out by two Justice League of America issues (#75 and #77) which directly addressed concerns about individual, personal accountability (a theme that would be re-visited a number of times ) as evidenced by the “new” Green Arrow coming to terms with his new place in the world in “In Each Man There is a Demon”, and the insidious perils of political manipulation in a story “Snapper Carr – Super Traitor!”. Both stories were written by Denny O’Neil, with art chores by Dick Dillin and Joe Giella.

|

| © DC Comics. JLA #75. Green Arrow gets introspective. |

|

| © DC Comics. JLA #77. "Snapper Carr - Super-Traitor!" |

|

| © DC. Green Arrow hits out at the "dumbing down" of society. |

1970 Going mainstream with Race, Pollution, Native American Rights

As the year turned to 1970, some shaking out of the DC portfolio had taken place with the cancellation of Bat Lash as of issue #7, but the presence of “relevant” story telling was on the rise. February 1970 saw the first of a JLA two-parter focusing on the perils of pollution in Justice League of America #78 “The Coming of the Doomsters” (by Denny O’Neil, Dick Dillin & Joe Giella) , while over on Batman #219, the Neal Adams’ Christmas classic backup “Silent Night of the Batman” quietly slipped in some observations of street homelessness and GI’s returning from Viet-Nam, as written by emerging author and O’Neil protégé Mike Friedrich.

|

| ©DC JLA #78. "The Coming of the Doomsters" |

|

| © DC. JLA #78. Green Arrow takes on pollution |

March 1970 saw the second part of the JLA pollution story #79, “Come Slowly Death, Come Slyly”, and then in April 1970, Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76 took relevance to a whole new level as “Beware My Power!” exploded on comic-buyer’s senses , bringing together multiple themes already addressed by Denny O’Neil in the pages of JLA, but now cemented by the dynamic artwork of Neal Adams.

|

| ©DC. Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76 "Beware My Power" |

Then began a sixteen-issue run covering GL/GA #76-87, 89 and Flash #217-#219 with stories that were to directly address the full spectrum of social issues through the lens of the skepticism of Green Arrow, contrasted with the sometimes naïve conservative sensibilities of Hal Jordan. As the series got underway in the summer of 1970, the first issues to be addressed were racial discrimination, worker exploitation, the problems of Native American reservations , and the disposal of toxic waste. A heady brew. The agenda was clearly set, and other books in the DC were taking notice.

|

| ©DC. Lois Lane #106. Why did Superman build this machine? |

As the Autumn of 1970 came into view, two full years after the first Wonder Woman story set in the Age of Aquarius, DC’s other major female role-model Lois Lane started to demonstrate a similar social awareness, when in October 1970 she first embraced Women’s Lib by first charging Perry White with sex discrimination, and the following month decided to use a machine constructed by Superman to turn herself into a black woman so that she could embrace the Black Experience first-hand. This was a rather heavy-handed and patronizing, if well intentioned, piece by Robert Kanigher (“I am Curious (Black)”). Looking back now, the idea of assigning a morose, middle aged white male to write the story seems unfathomable. If published today, the cover was the epitome of “click-bait”.

As the year rolled towards a close, unbridled relevance was now featured as the main topic in two major comic books each month. In November 1970, while Lois was taunting Superman that she was black, the Justice League fought a villain who first wanted to enforce a peace serum on the global population, before deciding that mass genocide was a better way to address the world’s problems and start over in JLA #84 "The Devil in Paradise". This opus was the work of Bob Kanigher, Dick Dillin and Joe Giella, giving Bob Kanigher the honour of having two “relevant” stories on the stands in the same month.

Even Tomahawk, in its final few issues before becoming "Son of Tomahawk", was tailoring its Old West stories to address contemporary issues of race.

|

| ©DC Comics. A fine Neal Adams cover for Tomahawk #128 |

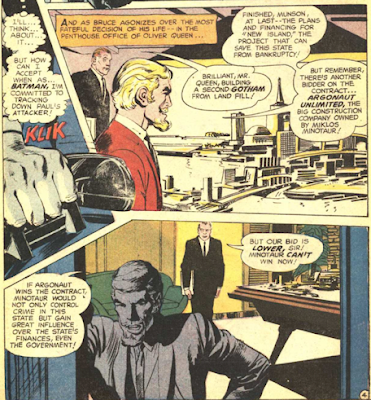

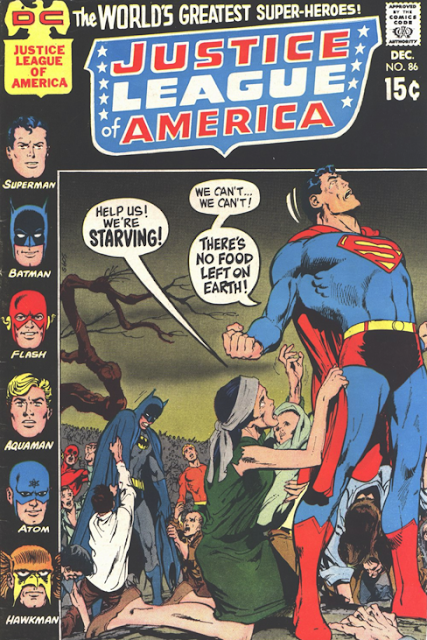

Dec 1970 can be seen as the start of "peak relevance" in DC comics. Wonder Woman and Lois Lane were reflecting the broader concerns of the younger generation, with Green Lantern/Green Arrow and Justice League of America as the backbone of “relevance” in comics, with a continuous stream of stories directly addressing hot issues. The perils of over-population were highlighted in GL/GA #81 "Death Be My Destiny" and a Justice League of America (JLA #86) featured a story about Food Supply in a tale called “Earth’s Final Hour” written by young Mike Friedrich (Denny O’Neil is billed as “script consultant”) and artwork by Dillin and Giella. Joining the band of relevant comics was the re-tooled “Son of Tomahawk” #131, inventing Hawk as a new counter-culture hero in the Old West, with modern sensibilities and dyed hair.

|

| ©DC Comics. GL/GA #81 "Death Be My Destiny" |

|

| ©DC JLA #86. "Earth's Final Hour" |

1971 Population growth, Food Supply and the worst social evil - drugs!

March 1971 saw a Green Lantern story (#82) that again tackled the issue of personal integrity and responsibility, this time from Green Lantern’s point of view. The start of the decade was a time of self-analysis and the rise of the importance of the “shrink” in US culture, which made these stories of self-discovery so relevant. Over at JLA #88, "The Last Survivors of Earth", Mike Friedrich had written a story about the last survivors of Earth and questioned our over-reliance on technology.

Perhaps the well was running dry, or audience appetite for this kind of polemic was waning, but after March 1971, DC cut back to publish a maximum of one “relevant” tale per month, featured either in Green Lantern/Green Arrow or Justice League of America.

GL/GA #83 (May 1971) contained a story both lampooning Nixon and Spiro Agnew, while also showing how Carol Ferris’ paralysis , her physical disability, was not an impediment to success.

In June, JLA #90 ran a story about the importance of ecology “Plague of the Pale People” by Mike Friedrich. Over at GL/GA #84 - Green Arrow made unambiguous comments about the evils of a world overun by plastic, and the effect it has on our society, touching on topics of smog over company towns, and even citizen brainwashing. The mixing of different concerns into one story served to dilute the impact of each of the issues mentioned.

Already the stories were becoming more of a harangue than an enjoyable entertainment. All credit to Friedrich and O’Neil for their passion, but I suspect that the sales were starting to wane.

1971 was a pivotal year for comics publishing. Printing costs had spiraled ; the price of the traditional comics had risen from 10 cents to 12 cents to 25 cents for a 48-page comic. More content was needed to fill those pages. And so three years since Wonder Woman first set the ball rolling, August to December 1971 saw a brief resurgence with both the two-part Green Lantern/Green Arrow drugs issues (GL/GA #85 and #86) and a two-part JLA story with a plea for co-existence and listening to those whose language we cannot understand”Earth – The Monster-Maker” written by Mike Friedrich.

Mike Friendrich addressed the same themes in a two-parter Robin story the following months as a back-up in Batman #235 and #236 (“Society of Outcasts” & “Rain Fire”), drawn by Irv Novick & Dick Giordano, which highlighted the generation gap issues between hippies and the older conservative generation. The year was closed out with stories about Black Power in Green Lantern #87 which introduced John Stewart as Green Lantern’s back-up, and a tale reflecting on the situation of soldiers returning from Vietnam in Justice League #95.

1972 Running Out of Steam

As 1971 turned to 1972, DC took a rest from social messages, and the first three months of 1972 saw no direct stories concerning social issues. April 1972 then saw a brief resurgence with a story about corporate greed and corruption in GL/GA #89 (with arguably the finest final panel in any comic story I had read). In her own comic, Lois Lane walked out on her job at the Daily Planet, as the Lois Lane comic book came under the editorship of Dorothy Woolfolk.

|

| ©DC Comics. Green Lantern has had enough. |

But the resurgence was a false dawn, and we waited until issues cover-dated June 72 to read another Mike Friedrich-written plea about preserving the ecosystem, in JLA #99. Son of Tomahawk quietly ceased publication with #140.

|

| ©DC. Art in the Kubert style by Frank Thorne could not save Son of Tomahawk |

Relevance was not yet dead, but it was on life-support.

The commercial realities of the price of paper and printing had caused the 25-cent/52 pages comic to be scaled back to a slimmer 32 pages for 20 cents, and thus August 72 to Dec 72 saw the final Green Lantern /Green Arrow “relevant” story relegated to the back pages of Flash #217-219 in a story arc “The Killing of an Archer”, again focusing on the importance of taking personal responsibility. As the publication of this 24 page story was spread over the five months of three bi-monthly issues, the importance of relevance was clearly on the wane.

While the Flash issues were playing out, Oct 1972 saw the final issue of Lois Lane #127 to be edited by Dorothy Woolfolk, and with Dorothy’s exit any concerns about Women’s lib also disappeared from those pages.

Nov 1972 saw the publication of the last Women’s Lib version of Wonder Woman (#203) in a special “Women’s Lib issue!” before she returned to her Amazon garb and left the realm of the modern business woman behind. Dorothy Woolfolk had previously taken over as editor of Wonder Woman #197 in Nov 1971, but almost immediately passed control to Denny O’Neil with #199, in which issue Denny laid his cards on the table in the editorial about his view of Diane Prince as the modern woman. Despite his best intentions, his editorial reads as slightly sexist and condescending. But within a few issues, the stories became tighter, culminating with WW #203 as the “Women’s Lib Issue”, featuring a rendition of a Carmine Infantino lookalike as a magazine publisher. Denny’s full-page editorial is worth a read, and reading between the lines you can sense his unhappiness at having to hand-off to Bob Kanigher.

|

| ©DC Comics. Wonder Woman #203. "Women's Lib Issue!" |

And so almost five years after Woman Woman #178 ushered in the era of relevance in DC comics, it was only appropriate that Woman Woman should usher it out.

1973 - Don't Look Back in Anger

And that was pretty much it for “relevance”. Denny went on to handle a large portfolio of new books for DC (including The Shadow) and the social concerns of 1972 were swept away with the excitement of the new books of 1973. I did not notice the change of tone at the time.

The last word about Social issues was left to Batman on the final page of Batman #251, cover dated September 1973 , “The Joker’s Five Way Revenge” when the Joker slips up on a oil slick on the beach, allowing Batman to capture him. Batman laughs “I never thought you – my arch enemy – would make me grateful for pollution!”

|

| ©DC Batman #251. The last word on pollution. |

Now it is clear to see that "Relevance" had been the baby, the brainchild and the passion of Denny O’Neil, ably abetted by young college sophomore Mike Friedrich, and supported by long-time stalwarts Haney and Kanigher .

Neal Adams has received (and accepted) the lion's share of the credit for "relevance" in comics, and is without doubt the artistic name almost exclusively associated with “relevant” comics, but without the work of Dick Dillin & Joe Giella, Nick Cardy, Mike Sekowsky, Irv Novick and Dick Giordano, it would have been a much slimmer body of work.

When "Snowbirds Don't Fly" (GL.GA #86) won the 1971 Shazam Award for "Best Individual Story", New York Mayor John Lindsay wrote a letter to DC in response to the matter, commending them, which was printed in issue #86. Once DC had achieved National approval and exposure, wiser heads probably thought it was time to move on. Concerned that they might be perceived as preachy, the stories dialed back on social relevance.

Denny O’Neil did not abandon social commentary completely, but the storytelling became more nuanced. Looking back on his career in an interview with Gary Groth for The Comics Journal around 1980, Denny said “I liked conflict and turmoil when I was 25. I don’t know what it is about being 25, but you’re hungry for conflict, for turmoil, and you run toward it. When I was a newspaper reporter, a story involving that kind of thing had infinitely more appeal for me than a story, for example, I did about a lovely old Japanese gardener and his wife who were having a wonderful and tranquil old age. That was a real good story I did, and it was very moving, but I didn’t enjoy it nearly as much as I enjoyed the time that I got some real heavy dirt on the police department and I showed that these authority figures had really dropped the ball.”

“I’ve written a lot of scenes where people regret the fact that violence was necessary in a given situation. In one of the best stories I ever did, “There Is No Hope in Crime Alley,” the whole point of it is that the old lady who stayed in the slums and never raised a finger to anybody was a much greater hero than Batman — which he acknowledges on the last page. That’s the way I go with it.”

I encourage you to take the time to read the full interview that Denny did back in 1980 and released in full form in The Comics Journal #66 (September 1981), https://www.tcj.com/rationality-and-relevance-dennis-oneil/

For those of you interested in statistics, here is the breakdown of number of stories dealing directly with different social issues over that 5-year period of 1968-1973. None of those topics remain any less important in today’s world. These Bronze Age comic stories were positive and optimistic, in that they showed that these sometimes insoluble problems could be addressed if individuals were willing to put themselves on the line.

How did “relevance” in comics affect your world view? Is it time for modern comics to “grow up” again, or is the sanitized world of the DC and Marvel Comic universes the best place for our heroes to operate?