Superman’s career, from the very beginning in 1938 to a pre-reboot ending in 1986, reveals an interesting moral convergence of his inner and outer strengths.

To appreciate this, we must first lay aside the standard explanation for differences in the same DC characters across the decades; the multiple-universe concepts of Earth-1 and Earth-2.

The truth is more interesting.

Superman’s use of violence evolved in three

phases, driven by two outside factors.

The first phase was the most uncurbed

level. When Superman first appeared in Action Comics #1 (June 1938) the concept

of a hero meting out justice to evil-doers was a familiar one to readers of

popular fiction, especially of the pulp magazines. The Shadow gunned down

gangsters with monthly regularity. It would have been no surprise that, as

early as the second issue of Action Comics (July 1938) Superman was seen

hurling a torturer to his death.

[Action Comics #2, July 1938]

Superman seems to relish threatening

criminals with his super-strength, and they would be wise to not call his

bluff. These aren’t idle threats as a number of criminals died in these early

Superman stories, without due process.

[Action Comics #16, September 1939]

[Superman #2, Fall 1939 –reprinted from the newspaper strip]

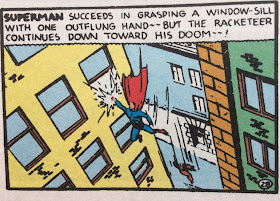

Also, on several occasions Superman

allowed, through inaction, for them to meet a horrible end.

[Action Comics #13, June 1939]

[Superman #2, Fall 1939 –reprinted from newspaper strip]

This first version of Superman doled out

his personal justice like Judge Dredd, performing executions of criminals as he

saw fit. To anyone brought up on the Silver Age and Bronze Age Superman, the

epitome of morality, these acts of manslaughter (if not murder) are a shocking

sight.

But very soon after this time, Superman’s

attitude towards violence changed.

[Superman #5, Summer 1940]

[Superman #5, Summer 1940]

By the summer of 1940, Superman is allowing

justice to be served by the law of the land. So what actually brought about

this second phase, this change of Superman’s mind?

Not specified within the narrative of the

Superman stories at the time, the answer must lie with the outside world, and

the imperative of maximizing financial success of the character for the owners:

most notably Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz. Once they saw the success that

they had in their hands, they were swift to exploit as many opportunities for

‘Superman’ as possible. Besides selling ‘Superman’ as a newspaper strip (the

original ambition for Superman by Siegel and Shuster), the obvious move was on

to radio – early films, cartoons, and later on to television.

The radio serial The Adventures of Superman

began regular broadcasts from February 1940, just 21 months after the first

appearance of Superman on the comic-book racks in May 1938 (although Action

Comics #1 was cover-dated June 1938).

When Siegel and Shuster had first signed

their contract to supply Superman to Detective Comics Inc. for publication,

Siegel had a relatively free hand to write the stories. Shuster supplied the

art (soon with the additional supporting artists in his ‘studio’: Paul Cassidy,

Jack Burnley, and – even this early – the distinctive 1950s/1960s Superman

artist Wayne Boring).

But once Superman’s unexpected success was

apparent to Donenfeld and Liebowitz, they knew that they needed better

editorial control over their lucrative comic books. They employed Whitney

Ellsworth to get a firmer grip on the material. He became the second editor of

Action Comics, replacing Vince Sullivan from Action Comics #21 (February 1940).

By this time, with a radio show, Superman’s

popularity would have been limited if his moral code was not acceptable for

family listening. It’s likely that word must have got back that Superman had to

stop killing crooks with such abandon. I suggest that this first outside factor

explains Superman’s change of attitude between the autumn of 1939 and the summer

of 1940 (by which time the radio show was in full swing).

These concerns anticipated the growing

alarm of parents who feared their children would be brutalized and corrupted by

the material in the ‘funny books’. The comics industry eventually founded the

Comics Code Authority in 1954, especially after the attacks by the psychiatrist

Fredric Wertham. (But as we have seen now, Superman’s publishers had reeled in his

more base instincts years before this happened!)

After this, hundreds of Superman stories

embedded this strict ethical code of behaviour into the bedrock of Superman’s

being: so much so that his oath ‘never to kill’ became a staple of Superman

comics throughout the Silver Age of Comics – and also the plot engine of a

number of stories themselves when he had to devise ingenious methods to keep

this oath, yet defeat his enemies.

(Another interesting by-product of

Superman’s new radio presence was the demise of Clark Kent’s editor in the

comics, George Taylor. Taylor’s last appearance was in Action Comics #30

(November 1940) and Perry White (just ‘White’ then) was there in the next

published Superman story in Superman #7 (November-December 1940). But the

character of Perry White, as Clark Kent’s editor at The Daily Planet, had

already first appeared in the second episode of the radio serial, broadcast

back in February of that year. This was a case of the comics being brought into

line with the radio show – as did also happen later with the introduction from

radio to the comics of Superman’s vulnerability: kryptonite.)

By the Bronze Age, the cultural landscape

of America had changed from the moral certainty of the Eisenhower era and the

depths of the Cold War in the 1950s. This became the second outside factor to

change Superman.

Vietnam and the countercultural pressures

of the 1960s and 1970s began to have their effect on Superman’s new generation

of writers. One of them was Denny O’Neil, who had begun to write the innovative

socially-aware Green Lantern/Green Arrow stories. He was brought in to renovate

the Superman title in 1970 by new editor Julius Schwartz, debuting with

Superman #233 (January 1971) with a story defining a new direction for the

character in ‘Superman Breaks Loose’. ((Spoiler Alert!)) The kryptonite on

Earth is rendered harmless to Superman, but at the end of the story arc – over

a number of issues – Superman himself is permanently physically weakened. Okay…

he was still ‘Superman’: he just couldn’t toss planets around as easily as

before.

After these physical changes, the moral

certainty of Superman himself was challenged. A notable story was published a

year later in Superman #247 (January 1972). Written by Elliot Maggin, ‘Must

There be a Superman?’ was an exploration of the problem of Superman always

being on hand to help planet Earth, thus potentially stunting the natural

development of humankind. Perhaps Maggin got the idea from Star Trek’s

well-known ‘Prime Directive’ – but no matter. He raised interesting questions

about the relationship between the helper and the helped.

But perhaps a more significant story was

also published in that landmark issue, one that marked a third phase in

Superman’s relationship with violence.

The first in a short-lived series ‘The

Private life of Clark Kent’, this Denny O’Neil written story describes how

Clark Kent defuses by persuasion the kind of situation that Superman would have

dealt with by force. Clark Kent muses, afterwards, that perhaps ‘Violence isn’t

always the answer’. Note that it’s ‘Violence’, not ‘Killing’. He’s moved closer

to Mahatma Gandhi’s personal practice of nonviolence with this new understanding.

Incidentally, that story also displayed another

change in prevailing attitudes since the early 1940s. In Action Comics #21 (February

1940) Superman is considering a problem as he sits at home smoking his pipe.

[Action Comics #21, February 1940]

In Superman #247 (January 1972) he wonders

if he’s been missing something by not trying tobacco – and the message to the

readers is clear!

[Superman #247, January 1972]

But returning to the issue of Superman’s

changing attitude towards violence and killing, it was the perceptive writer

Alan Moore who realized that, by the end of the Bronze Age, this was the foundation

on which this version of Superman rested. Remove that, and it would be enough

to end his career.

Moore got the chance to demonstrate this

when he wrote the two-parter ‘Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?’ in

Superman #423 (September 1986) and Action Comics #583 (September 1986). ((Spoiler

Alert!)) Moore’s plot contrives to force the immovable object (Superman’s ethical

code) to meet the irresistible force (the demand of the plot: he must kill the

newly totally evil Mr Mxyzptlk to prevent countless innocent deaths). The

immovable object breaks under the imperative of saving future lives, and

Superman must be no more.

[Action Comics #583, September 1986]

This shift, from having such a cavalier attitude

to criminals’ lives to Superman’s ‘oath never to kill’, illustrates a rather

different conception of strength than what is usual in super-hero comics.

In the Book of Proverbs (16:32), it’s

stated that ‘He who is slow to anger is better than a strong man, and a master

of his passions is better than a conqueror of a city’. This is summed up by the

sage Ben Zoma, who said, (in the Ethics of the Fathers 4:1): ‘Who is strong? One

who masters his evil impulse.’

Here we have a philosophy of self-restraint

as being the true marker of strength. Scale this up to the super-powers of a

Kryptonian under a yellow sun, and we can see how it would take a

super-strength of the mind, not the body, to resist the temptations on offer

when living as a Superman on a non-Super planet Earth.

Yet Superman showed this inner strength from

the very beginning, in his origin story. He was willing to live as a normal

person and not to use his super-powers for any kind of self-aggrandisement,

self-enrichment or power over others.

34 years later, his attitude towards his

outer, physical strength finally caught up with that inner strength. He finally

accepted that violence was not necessarily the answer to doing good – even if

you’re Superman.

copyright. Nigel Brown